Body Language(s):

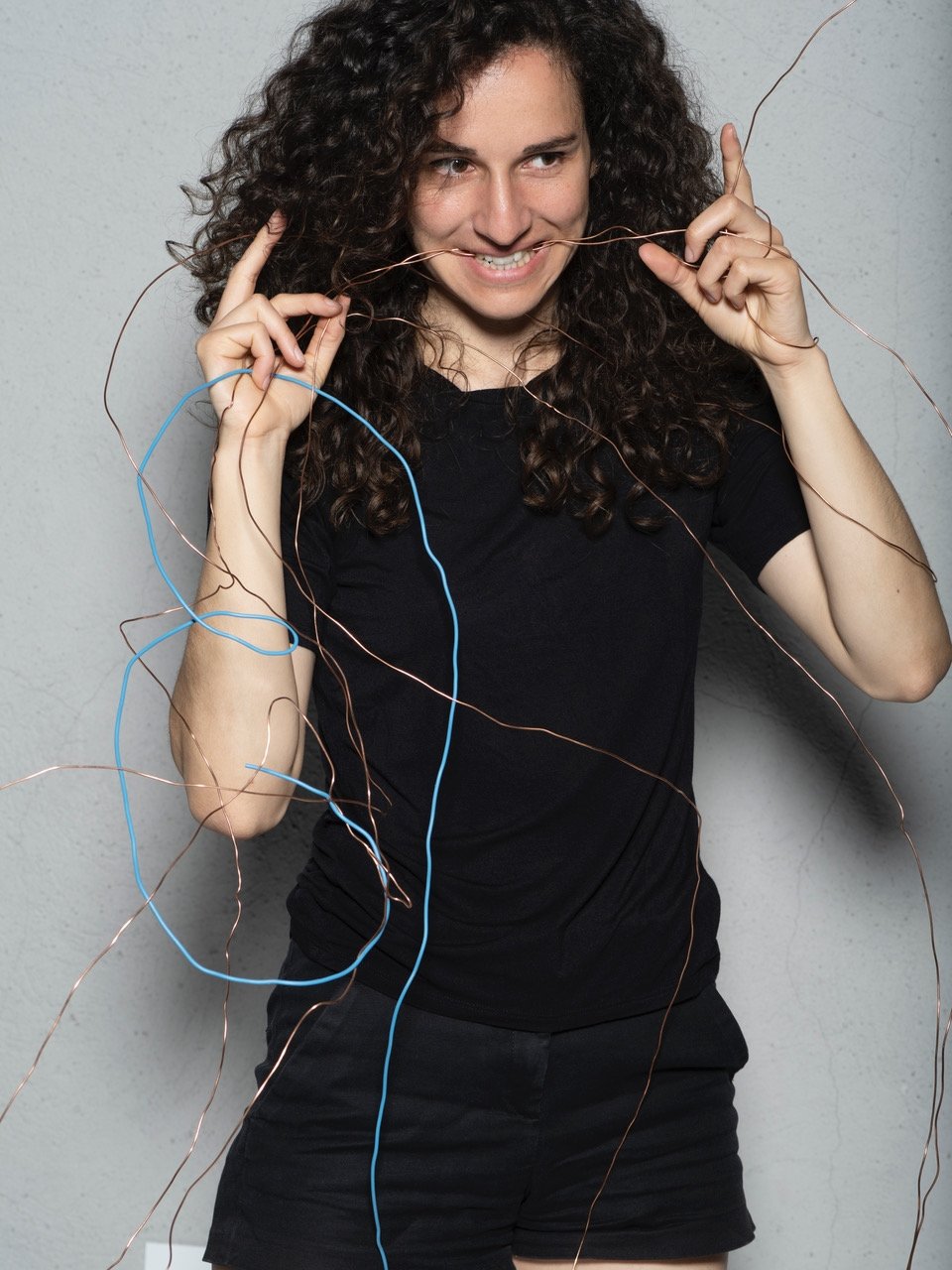

a conversation with Sara Lanner,

an interview by Cindy Sissokho.

This interview is presented as an ‘in conversation’ with Vienna based artist Sara Lanner whom I’ve had the chance to meet in Vienna in September 2021. Our exchanges delve into the socio-political questions that are central to some of her series of works through a multidisciplinary practice that genuinely intersects dance, performance, sculpture and installation. I selected specific performances: MINE, Mother Tongue and Etiquette of Tongues for the urgency of the discourse around extractivism on one side and the collective questions about the politics of language and notions of identity and belonging on the other.

Cindy Sissokho (CS): Who is Sara Lanner? And how do you describe your artistic practice?

Sara Lanner (SL): That’s always a big question! The conventional answer is 'a choreographer and visual artist' or 'a dancer and performance artist' - you may choose! But a more poetic answer would be that she is someone who likes to observe the world around her, someone who regularly gets lost in evening-long conversations about it with friends and someone who is particularly good at translating these impressions into kinesthetic experiences for an audience.

My practice always relates to my background as a contemporary dancer combined with the interest for aesthetic concepts and material studies deriving from the visual arts. Observing the performativity of the body, of objects or language will thus always be part of my approach. Some of my works seem to start directly with and from the body. However, many of them start from observing the performativity of objects (which I might build by myself), a specific material or philosophical concepts. By touching them and interacting with them, understanding which associations, movements, memories and images they evoke by embodying and performing them in the space, I create my choreographies, installations, photography or video works.

From time to time other approaches in my practice disappear and reappear such as singing and drawing but the basis of it remains a somatic and performative approaches.

CS: How did contemporary performance, working through and with body movements come about for you? You also talk about ‘the self as social choreography” and work within a diverse range of contexts, could you tell us more about this?

SL: As much as we are co-creators of the world that surrounds us, we are being shaped by it too. I believe that all our experiences are saved as memories in our bodies and furthermore that these embodied stories manifest in our habits, the way we move, think or talk. In my choreographic work I try to deconstruct story by story, layer by layer, so I can unfold and refold my/other personality/personalities and look at it/them from many different angles. It is a state, which is never ultimately fixed but in a constant movement (choreography) of reshaping itself.

In my artworks this idea reappears in my movement language that sometimes looks like a collage of many different bodies. You can also find it within the foldable objects that I create that are made of textile, wood or cardboard, and finally how I work with language and its repetition, variation and fragmentation.

CS: Collaboration and making space with others are essential within your performative practice, and as an artist, you are also involved with pedagogy by teaching others. How do your creative processes differ when producing a solo or a collective piece? And how does one or the other become essential when thinking about a new piece of work?

SL: Before I started working with performance, I felt the need to be by myself, alone in a dance studio for a year and a half. It is only then that I was ready to work with or for others. I enjoy how collaborations make me delve into topics I would not come about by myself and the work within artistic research labs makes me feel high sometimes; while in projects where I am the artistic lead, I have the possibility to make the most precise decisions according to my own convictions. I seem to prefer the latter as it seems to be easier but really it is also lonelier and the power of a group or collective is not to be underestimated.

I am glad that my way of working offers this variety to me. Furthermore, I also enjoy being a performer and dancer for others, to be part of enabling an artwork by offering your skills and thoughts.

CS: In this body of work, you re-appropriate the word 'mining' as an extractive (body) language where the information is purely communicated from the contact from body to body: yours and of your collaborator. The bodies move from being tightly linked together to detachment. They are also generating an intimate connection as they are in contact with a range of objects that were made, found, or modified - all reflecting upon the ethical implications of global mining processes as a collective responsibility. How did you grow your relationship with the subject of extractivism as part of your own context and artistic practice too?

SL: 'Mining' interest me from a material, immaterial or even metaphorical perspective. The term 'mining' is connoted with materiality, resource usage and wastage, often with violent appropriation and over-dimensional transformations. But it is also incorporated into our immaterial world - data mining, for example, where our information and decisions have become 'mined' resources.

All these products, processes and experiences do not only shape our personal and individual identity but even more our cultural identity. Therefore, from a performative perspective, I am interested to see how this manifest in our behaviours and mindsets. One could say that I am 'mining' for this information located within our bodies. In the performance my co-performer Costas Kekis and me approach the body neither as a romantic storyteller nor as being violent towards each other. Our approach was to try to understand how a very deep kind of touch can happen without harming, hurting or cutting the body open. And perhaps by doing so we can learn something about the ethical implications of using each other as a resource and how to deal with the ambivalence that comes about the whole topic of 'mining'.

CS: Could you tell us more about the hierarchy of these objects and the bodily experience you anticipated and didn’t anticipate as you encounter them during the performance?

SL: I wanted to translate the observations (mentioned in the previous response) into a choreography for two performers as a way to show notions of dependency and collaboration which are connected to mining. One can see the performers pushing or pulling each other, sometimes protecting each other or protesting together.

But actually I began by getting in touch with the objects and 'raw' materials appearing in MINE - I started by 'mining' displays from old mobile phones, copper wires from old WIFI cables, collected stones in Chinese landfills or salt mines in Salzburg. Later on, this material also informed our movement. Furthermore, we also looked at archival photography from miner’s protests or photographic works by artists, taken in mines. There is no hierarchy for me between the different materials, may it be movement, objects or images. They all become performers which tell their own stories.

However, something I did not expect was the slowness of our movements. Throughout the performance we seem to be moving in slow motion, balancing on shaky objects that make loud noises, or you see us slowly melting, freezing or hugging, grabbing and pulling each other with a high physical tension. I guess it is due to the dramaturgical tension that is needed for these very somatic choreographies to become tangible for an audience.

CS: As the performance ends - and this is also the case for other performance work - you allow for the objects to have an afterlife within the location of the performance, and can somehow be looked at with new meanings, by themselves. How do you negotiate the medium of performance and visual arts within this specific body of work and within your practice too?

SL: I believe that when you observe a certain selection of objects and their materiality, they start telling their own stories, as much as the performing bodies do. Later this year I performed the work Mining Minds at brut Vienna, a full-on dance piece on a conventional black box stage. And still, the space concept and the objects are being handled almost as performers of their own and I spent a lot of time creating the space concept in relation to the dance and choreography, also asking what imprint our performance leaves on some of the material, after we walked on it or performed with it.

Within my practice I love to challenge the conventional ways of handling ‘a stage‘ or an ‘exhibition space‘ - therefore some of my works are transitioning from black box to white cube or vice versa or even sometimes into a public space. It is not always possible but when it happens, I consider it as a further manifestation of the initial idea. What I also appreciate about it is to see how a work grows and seems to start breathing while you are further developing it.

I often tried to understand what fascinates me about states of transition and one of my explanations is that I grew up bilingually - Italian and Austrian - and thus within two cultures. Even my father is an interpreter and collaborated with my mother as a translator. The idea of shifting or mediating between multiple contexts and confronting yourself with the ‘foreign’ has always been part of my reality and way of thinking. This is specifically reflected into one of my works untitled Mother Tongue.

CS: The common denominator of the two performances is the durational usage of the tongue in a repetitive manner and the imprint it leaves on the space. The tongue becomes a substitute muscle to express yourself non-verbally in the form of writing - it is a predominant metaphor within both bodies of work in exploring identity and belonging. What are the other forms of language and discourses, the unseen as one watches the performance, that are created, communicated and felt as you perform?

SL: Both performances develop an intimate link between the experience of the ‘now‘ in relation to a (collective) history, including our responsibilities towards each other. For me Mother Tongue is also about a silent protest, a tongue written graffiti or abstract tongue painting, speaking about gender stereotypes in society. Only some months after the performance was created, I realized I did it during a time when some populist and conservative parties started to gain an up-draft again in Austria and narratives such as of splitting schoolchildren into groups according to their mother tongues or cancelling the internal ‘I’ (an indicator for female forms of nouns in German language) in the Austrian military, were highly discussed topics in the media.

What connects it to Etiquette of Tongues is the attempt to perform the gap between self and other - an attempt to find a language for that, in which I can only fail as it is an ongoing search. So, I guess it is also about how to integrate something that we perceive as foreign or uncanny but is still intimate in our understanding of reality.

When referring to the uncanny, Etiquette of Tongues - which is basically an amicable/friendly dialogue with a wet specimen, the tongue of a day worker - also speaks about the persistence of the body and the stories embodied within it. It makes me reflect not only on life and death but also on immaterial or metaphorical forms of ‘existing’ or to project myself into a more distant future.

CS: In Mother Tongue specifically, how do you convey the role of the audience in understanding the role of language within politics of identity and belonging?

In Mother Tongue the audience might serve as a representative body, talking about collective bodies, imagined communities, the foreign or alien - categories which are being conveyed strongly through the use of and identification with a specific kind of language, in its broadest sense. I am writing on a gallery wall for almost an hour with my tongue. Repeating the words mother tongue, that slowly drift into a poem with variation (MOTHER TONGUE, MY OHTER TONGUE, OR HERE OR THERE, MY TONGUE, HER TONGUE, THEIR MASSIVE TONGUE…); the letters turn into abstract signs or paintings. Sometimes I mirror the text or start writing from right to left. It is a quite precise dramaturgy in terms of what I am writing how and where. Given the fact that it takes time to write with your tongue and it takes patience to wait for the next word until it is fully written, gradually a very clear political but yet poetic narrative appears and stays like an imprint in the spectator’s mind, as everyone of us has some kind of experience with language or the absences of it.

Some audience members told me they would start asking themselves which languages the other audience members might speak or where they come from. And how they construct their reality based on the language(s) they speak or don’t speak or whether they really ‘know‘ their language.

CS: What are you working on at the moment, is there anything you would like to share that you are inspired/keen to work on in the (near) future?

SL: To keep the tension something will be kept a secret! But - so much can be said - I will continue working on the topic of 'mining' for a little longer. One more approach will be a written thesis on my artistic and theoretical endeavour, including examples of related artworks by other artists.

Also, I want to further develop a practice of fragmented speaking, which appeared already in 2018 in my solo performance Guess What. For the first time in a long time, I recently reconnected to texts written by A.I.s and performed parts of it within the group exhibition connections unplugged, bodies rewired at das weisse haus (2021), which dealt with topics of (post-)digital intimacies.

Vienna & Nottingham | December 2021